Whooping it up in `Des Moines’

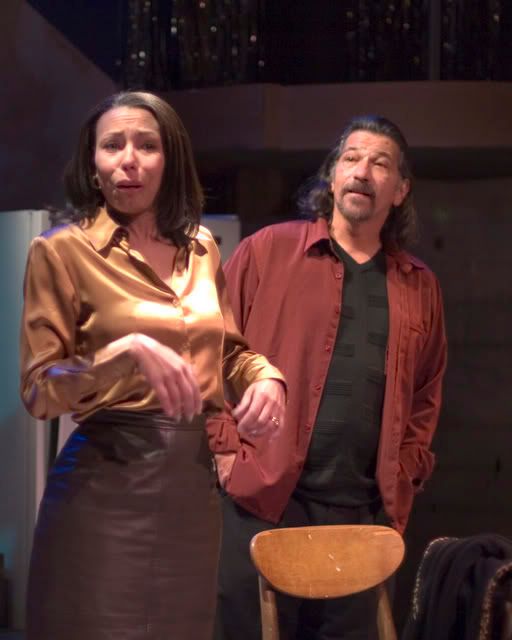

Campo Santo, Denis Johnson go a little crazy in IowaThree and 1/2 stars Comic, dramatic depth charge There’s a lot of wonderful weirdness in Denis Johnson’s Des Moines.The play had its brief, three-performance world premiere last weekend, not at Intersection for the Arts, the usual home for Campo Santo works. This season is all about breaking patterns and trying new things (the slogan is: “New Definitions of Theatre, Don’t Let the Evolution Happen Without You”).So Des Moines unfolded in the warehouse-y confines of artist John Gruenwald’s Gruenwald Press, a South of Market spot that required audience members to ride a freight elevator one floor up to the show.Before the show began, the audience mingled in the space – crowded with a variety of sofas, stools, chair and pillows on the floor – partaking of the hors d’oeuvres buffet and the open bar while the Howard Wiley Duo played some smoky jazz in the corner by the windows.Once settled into the hodgepodge of seats, the audience trained its attention on Leslie Linnebur and Joshua McDermott’s set: an average kitchen in Des Moines, Iowa. The one thing this kitchen had that kitchens in Iowa most likely do not: audience members seated in it.And at Sunday’s performance – closing night – author Johnson was seated in the kitchen, so we had the pleasure of watching the play and watching the playwright watch the play (he liked it, he really liked it).With each new play, starting with 1999’s Hellhound on My Trail through 2004’s Psychos Never Dream, Johnson seems to rattle the theatrical cage even more.Des Moines is a curious work. It begins in complete naturalism as husband and wife Dan (Luis Saguar, above right) and Marta (Jeri Lynn Cohen) deal with everyday things, like Dan’s loathing of margarine. He lectures Marta that “oleo” means “made of oil.” She’s heard it all before, which is why she buys butter. “You like it. I got it. Now eat it. I love you,” she says.From the first, this 85-minute “exploration of the damaged American soul,” as the program puts it, obsesses over mortality. Dan had a passenger in his cab, a woman recently widowed when her husband died in a plane crash, and she was obsessed with finding out her husband’s last words and thought maybe the cabbie could provide them.Turns out the husband was a step ahead of her and had put a note in his pocket that read: “If I die now, my last words were: Orange juice, please.” Then, for some strange reason, the widow left her husband’s wedding ring in the cab.Back in the kitchen, Marta announces she has some news and one of the local priests, Father Michael (Cully Fredricksen), is coming over. When Marta tells Dan that she has between two and four months to live, she turns to the priest for guidance and comfort.“There’s very little to say,” he says.“But to have a priest say it is something,” Marta says.Desperation, mortality and the need for meaning and release flood into the kitchen, and that’s just the start. The priest is a cross-dresser, and Dan and Marta’s grandson, Jimmy (Max Gordon Moore), was paralyzed during the waist down during his sex-change operation.While Dan and Marta are out buying beer and whiskey to make depth charges (shot glass full of whiskey dropped into a glass of beer, aka a boilermaker), the widow, Mrs. Drinkwater (Margo Hall, above left) shows up to reclaim her husband’s wedding ring.What she finds is Jimmy in his wheelchair wearing a tight ‘70s dress, full makeup, Jackie O sunglasses and long brunette wig, and Father Michael wearing rouge, eye shadow and lipstick.The priest, the transsexual and the widow get a head start on the depth charges, so when Dan and Marta return, the party is in full swing. Next thing you know, the karaoke machine is on (terrific sound design by Gustavo Pastre and Drew Yerys), and Jimmy is singing “Folsom Prison Blues,” the priest recites a dramatic monologue to “Love Me Tender” and the widow gets down and dirty to “Kansas City.”Then the weirdness starts, and I’m not talking about Marta screaming, “The widow is a whore! The black widow is a whore!”Director Jonathan Moscone doesn’t usually traffic in onstage weirdness, and that’s a strength here. When Johnson’s text veers out of naturalism and into dream chaos, Moscone’s firm hand -- and the good will he has established with the audience through strong direction and excellent performances – keeps the play from spinning into self-indulgent whimsy and tragedy.Events in the last scenes of the play may be inscrutable, but we’ve come to like this odd assortment of people so conveniently thrown together for a collective dark night of the soul.Des Moines hasn’t quite found its ending yet, but the play leaves its audience with an electrical charge that crackles with humor, mortality and the need for community – in a depth charge, Iowa sort of way.For more on Intersection for the Arts and Campo Santo’s fall 2007 events visit www.theintersection.org.

There’s a lot of wonderful weirdness in Denis Johnson’s Des Moines.The play had its brief, three-performance world premiere last weekend, not at Intersection for the Arts, the usual home for Campo Santo works. This season is all about breaking patterns and trying new things (the slogan is: “New Definitions of Theatre, Don’t Let the Evolution Happen Without You”).So Des Moines unfolded in the warehouse-y confines of artist John Gruenwald’s Gruenwald Press, a South of Market spot that required audience members to ride a freight elevator one floor up to the show.Before the show began, the audience mingled in the space – crowded with a variety of sofas, stools, chair and pillows on the floor – partaking of the hors d’oeuvres buffet and the open bar while the Howard Wiley Duo played some smoky jazz in the corner by the windows.Once settled into the hodgepodge of seats, the audience trained its attention on Leslie Linnebur and Joshua McDermott’s set: an average kitchen in Des Moines, Iowa. The one thing this kitchen had that kitchens in Iowa most likely do not: audience members seated in it.And at Sunday’s performance – closing night – author Johnson was seated in the kitchen, so we had the pleasure of watching the play and watching the playwright watch the play (he liked it, he really liked it).With each new play, starting with 1999’s Hellhound on My Trail through 2004’s Psychos Never Dream, Johnson seems to rattle the theatrical cage even more.Des Moines is a curious work. It begins in complete naturalism as husband and wife Dan (Luis Saguar, above right) and Marta (Jeri Lynn Cohen) deal with everyday things, like Dan’s loathing of margarine. He lectures Marta that “oleo” means “made of oil.” She’s heard it all before, which is why she buys butter. “You like it. I got it. Now eat it. I love you,” she says.From the first, this 85-minute “exploration of the damaged American soul,” as the program puts it, obsesses over mortality. Dan had a passenger in his cab, a woman recently widowed when her husband died in a plane crash, and she was obsessed with finding out her husband’s last words and thought maybe the cabbie could provide them.Turns out the husband was a step ahead of her and had put a note in his pocket that read: “If I die now, my last words were: Orange juice, please.” Then, for some strange reason, the widow left her husband’s wedding ring in the cab.Back in the kitchen, Marta announces she has some news and one of the local priests, Father Michael (Cully Fredricksen), is coming over. When Marta tells Dan that she has between two and four months to live, she turns to the priest for guidance and comfort.“There’s very little to say,” he says.“But to have a priest say it is something,” Marta says.Desperation, mortality and the need for meaning and release flood into the kitchen, and that’s just the start. The priest is a cross-dresser, and Dan and Marta’s grandson, Jimmy (Max Gordon Moore), was paralyzed during the waist down during his sex-change operation.While Dan and Marta are out buying beer and whiskey to make depth charges (shot glass full of whiskey dropped into a glass of beer, aka a boilermaker), the widow, Mrs. Drinkwater (Margo Hall, above left) shows up to reclaim her husband’s wedding ring.What she finds is Jimmy in his wheelchair wearing a tight ‘70s dress, full makeup, Jackie O sunglasses and long brunette wig, and Father Michael wearing rouge, eye shadow and lipstick.The priest, the transsexual and the widow get a head start on the depth charges, so when Dan and Marta return, the party is in full swing. Next thing you know, the karaoke machine is on (terrific sound design by Gustavo Pastre and Drew Yerys), and Jimmy is singing “Folsom Prison Blues,” the priest recites a dramatic monologue to “Love Me Tender” and the widow gets down and dirty to “Kansas City.”Then the weirdness starts, and I’m not talking about Marta screaming, “The widow is a whore! The black widow is a whore!”Director Jonathan Moscone doesn’t usually traffic in onstage weirdness, and that’s a strength here. When Johnson’s text veers out of naturalism and into dream chaos, Moscone’s firm hand -- and the good will he has established with the audience through strong direction and excellent performances – keeps the play from spinning into self-indulgent whimsy and tragedy.Events in the last scenes of the play may be inscrutable, but we’ve come to like this odd assortment of people so conveniently thrown together for a collective dark night of the soul.Des Moines hasn’t quite found its ending yet, but the play leaves its audience with an electrical charge that crackles with humor, mortality and the need for community – in a depth charge, Iowa sort of way.For more on Intersection for the Arts and Campo Santo’s fall 2007 events visit www.theintersection.org.