Crowded Fire: Please sir, may I have some Mao?

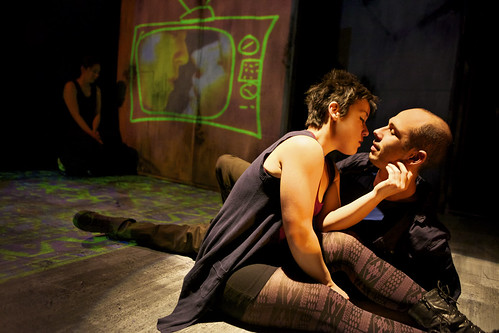

Cindy Im (far left), Anna Ishida (center) and Wiley Naman Strasser blur the line between theater, reality and revolution in the West Coast premiere of Christopher Chen's The Hundred Flowers Project. Below: The avant garde theater group devises a play about Mao Tse Tung using their "patented zeitgeist melding" process. From left: Wiley Naman Strasser, Ogie Zulueta, Charisse Loriaux, Anna Ishida and Will Dao. Photos by Pak Han

Cindy Im (far left), Anna Ishida (center) and Wiley Naman Strasser blur the line between theater, reality and revolution in the West Coast premiere of Christopher Chen's The Hundred Flowers Project. Below: The avant garde theater group devises a play about Mao Tse Tung using their "patented zeitgeist melding" process. From left: Wiley Naman Strasser, Ogie Zulueta, Charisse Loriaux, Anna Ishida and Will Dao. Photos by Pak Han

If Apple or some other high-tech giant was really smart, really forward thinking, they'd head down to the Thick House and check out the West Coast premiere of Christopher Chen's The Hundred Flowers Project, a play that not only has a lot to say about our instantly archived society and its millions of digital histories but also utilizes technology in a fascinating way.

There's something utterly primal about the premise of this Crowded Fire/Playwrights Foundation co-production: members of a San Francisco theater collective gather to create, in the most organic, zeitgeist-melding way, a dazzling piece of theater about the life and rule of Mao Tse Tung that has deep metaphorical connection to our own times. These theater folk are pretentious – the words "zeitgeist" and "congealing" are used so often they may cause indigestion – but they're also real artists trying to create something new and interesting and meaningful.

Their leader, Mel (Charisse Loriaux), invites everyone to continue adding ideas to the group Google Doc, and as she incorporates those ideas, along with those inspired by group discussion, the actors read the updated text from their smart phones while they rehearse. The tech aspect of the show, involving dramatic lighting (by Heather Basarab) as well as live and pre-recorded video (designed by Wesley Cabral), is also created on the fly (it's more organic that way, naturally).

Every once in a while, something weird happens. A big sound erupts (sound design by Brendan Aanes), the cast goes through a jerky modern-dance-like spasm (Rami Margron is the movement coach), and reality has shifted. At first these shifts take us more speedily through rehearsal so we can catch up on all the gossip like who used to sleep with whom and what the real power dynamics are in this collective.

But then the shifts start to get more serious as we experience more of the play and begin to see how Mao's rule, likened to a work of theater itself, really does have parallels in a modern world where we create, share and, perhaps most importantly, edit our own histories as we're living them.

Chen's script makes some tricky twists and turns throughout its swift two acts dispatched in just over an hour and a half. There's some deep intelligence at work here but also some sly humor to keep the pretension away, at least until it can't. There are some dangerous dips into near melodrama, but director Desdemona Chiang and her astute cast of six keep the play crackling until Act 2 finally dives into some murky waters.

Two of the best scenes involve beautifully integrated video. I must confess here that I have an aversion to video on stage because I go to theater specifically to see LIVE people interacting with other LIVE people. But this play is about, in part, our almost obsessive need to record and archive our lives. So, at a certain point, when memories have become absent or unreliable, former lovers Mike (Wiley Naman Strasser) and Lily (Anna Ishida) are back in each other's arms, literally. They're dancing and throwing each other around and pretending to fly, all the while recording themselves with their iPhones, and the live video from their phones is projected on the walls of Maya Linke's set.

Later on, after some time has gone by, Mike and his wife (Cindy Im) settle into a life of effortful domestic bliss. Their home is depicted in video renderings of a child's drawing, and on the pretend TV we see the couple in the near future, while their live, present-day selves struggle to get to that near future.

Another video moment with great potential that isn't fully realized involves video as a new form of masked drama (the Greeks would have loved this). An actor playing Mao (Strasser) is captured on video, while the video of his face is projected onto the sheet-shrouded head of another actor. The effect is a little like those creepy/fascinating talking mannequins at the deYoung's recent Jean-Paul Gaultier show (see video here).

The Hundred Flowers Project, for all its intellectual zest and meta-theatrical zing, makes constant jokes about succumbing to traditional narrative structures but ultimately falls into a humorless home stretch that dulls some of the thought-provoking fun that has come before. But this is still a fascinating, even compelling piece of theater that feels like it really is about the here and now. OK, OK. You might even say it actually taps into the zeitgeist.

[bonus interview]I chatted with playwright Christopher Chen and director Desdemona Chiang for a feature in the San Francisco Chronicle. Read the story here.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Christopher Chen's The Hundred Flowers Project, a co-production of Crowded Fire Theater Company and Playwrights Foundation, continues through Nov. 17 at the Thick House, 1695 18th St., San Francisco. Tickets are $10-$35. Call 415-746-9238 or visit www.crowdedfire.org.